Introduction

2021 could prove to be a pivotal year in the fight against climate change. With the crucial climate summit, the 26th Conference of the Parties (better known as COP26), happening in November this year, governments around the world are stepping up policy commitments to combat global warming. Just as pledges made in the run-up to the COP21 summit in Paris in 2015 were a crucial step in creating a trans-national response to climate change, we expect COP26 to be equally important in terms of driving specific targets about how these commitments will be achieved in practice.

In our first paper on climate change last year, we outlined the scientific factors driving the change, the risks associated with rising global temperatures and the challenges of limiting further global warming.

We also introduced the concept of ‘net zero’. In this, the first in a series of papers, we will explore the meaning and necessity of having a net zero ambition. In our subsequent papers we will then look at the challenges (technological, political and social), the opportunities, and the role that corporates and the financial services industry can play in achieving this goal.

Why is net zero needed?

Climate science is clear that global warming is directly linked to the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Since the pre-industrial era, humans have emitted 2,400 metric gigatons of heat-trapping carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere1, predominantly from the use of fossil fuels and land use change.

This has so far resulted in a rise of more than 1°C in average global temperatures above the pre-industrial levels. Without action, the rate of increase in temperatures will continue to rise to at least 3°C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century – a trajectory which incurs increasingly catastrophic events and irreversible physical damage to the planet, as well as presenting an existential threat to human life2.

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, countries agreed with the urgent need to hold ‘the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels’ but also ‘to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’. The presentation of further scientific evidence (most notably from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report in 20183) reinforced the importance of aiming for the lower 1.5°C rise, seeing this as a threshold limit above which the physical risks of climate change become far more devastating in their impact4.

However, halting this rise is given greater urgency by the fact that we are currently already at a level of warming of 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels. In order to limit climate change to 1.5°C, net CO2 emissions will need at some stage to fall to zero – hence the term net zero. Given the severity of the climate challenge presented and the current trajectory, we believe that breaking the link between carbon emissions and economic/population growth requires a system-level approach to address the challenges presented5.

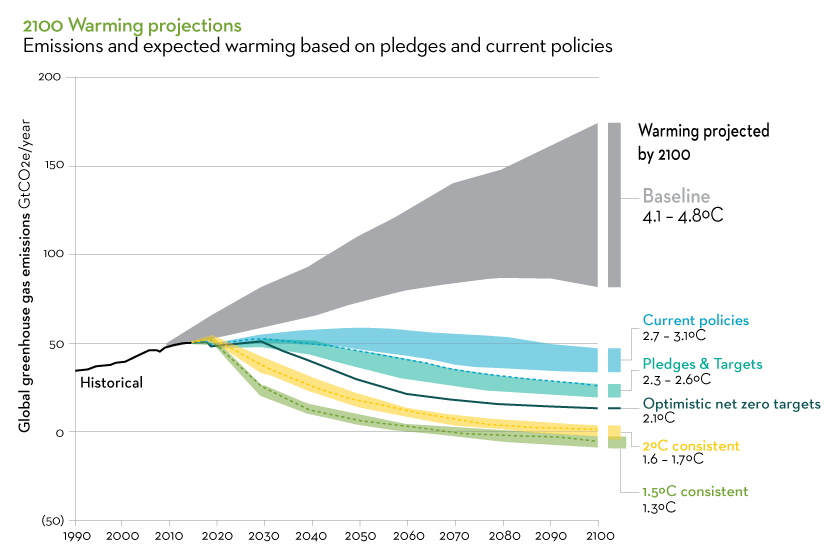

Source: Climate Action Tracker: https://climateactiontracker.org/media/images/CAT-2100WarmingProjectionsGraph-PNGLarge500-202.original.png

Policy makers should be emboldened by signs of progress on both the emissions trajectory and of the falling cost of getting to net zero.

What do we mean by Net Zero?

A gross-zero carbon target would mean reducing all emissions to zero. This is not realistic, so instead the concept of a net-zero target recognises that there can continue to be some emissions, but that these need to be fully offset. Net zero refers to achieving an overall balance between emissions produced and emissions taken out of the atmosphere.

This can mean either reducing emissions or offsetting these through removals of emissions from the atmosphere, predominantly through natural carbon sinks such as oceans and forests but also potentially through storage and the creation of artificial sinks6. Net zero also encompasses the idea that not all industries can have zero emissions and that these will have to be offset elsewhere.

The longer this takes to occur and the greater the level of emissions in the intervening period, the more significant the impacts of climate change will be. In general, science concludes that damaging impacts increase with the extent of global warming. In addition, the relationship to temperature increases is not necessarily linear; doubling the temperature rise may more than double the scale of a given impact. In addition, higher levels of warming raise the risk of passing ‘tippingpoints’ which can either lead to irreversible impacts or amplification of climate change7. The IPCC special report in 2018 on climate change highlighted significant differences in negative outcomes from keeping warming to below 1.5°C versus 2°C. For example, the proportion of the population exposed to severe heat is 2.6x worse in a 2°C world compared with a 1.5°C one. Sea-ice-free summers in the Arctic are 10x more likely and the ecosystem impact on species loss is 2–3x worse in a 2°C world8.

The 2018 IPCC special report highlights five key areas for concern that have a tipping point in severity as we cross the 1.5°C threshold in areas such as ecosystem loss, extreme weather and an impact on vulnerable communities particularly in developing economies. A changing climate leads to changes in the frequency, intensity, spatial extent, duration, and timing of weather and climate outcomes, and can result in unprecedented extremes9. There are also significant climate-related risks to health & livelihoods from a warming planet. Risks related to food security, water supply, human security, and economic growth are projected to increase with global warming of 1.5°C and increase further with a 2°C10 rise. Limiting global warming to 1.5°C, compared with 2°C, could reduce the number of people both exposed to climate-related risks and susceptible to poverty by up to several hundred million by 205011.

This evidence adds to the need for an urgent call to action among all actors to work together to craft tangible and credible real-world targets to achieve the aim of limiting warming to 1.5°C12.

The path to 'Net Zero'

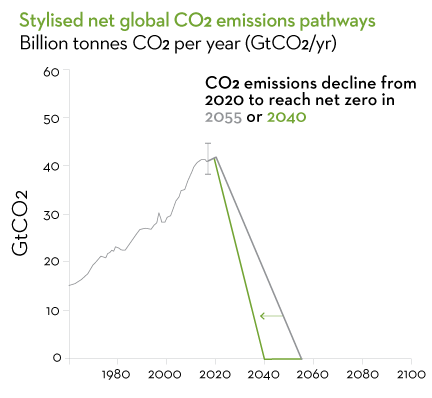

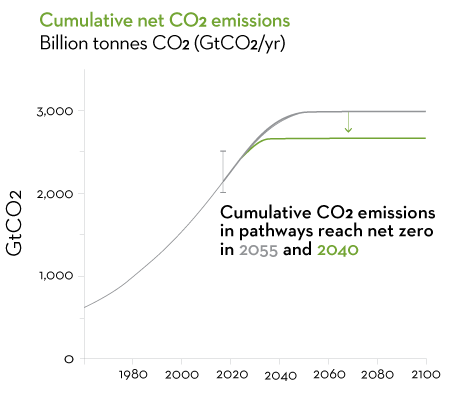

The ambition of limiting warming to 1.5°C requires net zero carbon emissions to be achieved between 2040 and 2055. The 2018 IPCC special report also discusses two types of pathway for stabilising global warming at 1.5°C from 2100; those that always keep below this temperature and those that overshoot it, with the temperature then being reduced towards the end of the century with substantial use of negative emissions13. Overshoot pathways carry greater risks of triggering potentially irreversible events such as runaway ice-sheet melt or species extinctions. Most net zero targets are made in an effort to avoid this.

The 2018 IPCC special report also gave an outline of what was required in a tangible sense to meet this deadline and provides perspective on what this means in terms of the assumed carbon budget until these thresholds are crossed. The report showed that the budget (the amount of carbon we can continue to release) for a 66% chance of remaining below 1.5°C amounts to 420GtCO2 – or 10 years’ worth of current emissions. Similarly, the budget for a 50/50 chance of exceeding 1.5°C is increased to 580GtCO2 – 14 years of current emissions14. Although an improvement from the prior Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), this still requires a rapid and decisive shift in decarbonising the global economy to meet this revised budget with an aim to reach net zero between 2040 and 2055.

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report 2018; https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/

The 2018 IPCC special report acted as a watershed moment in clarifying the extent of action required to get onto a pathway consistent with keeping warming well below 2°C as set out in the Paris Agreement and the benefits of substantially reduced risk if climate change was restricted to the more ambitious target of 1.5°C. This clarity of message is important in terms of being a guiding principle for countries to significantly step up their commitments as we approach COP26, with this being the last significant opportunity to increase their nationally determined contributions (NDC’s) to curbing emissions before the Paris Agreement enters its implementation phase15. This has created a strong momentum in the ambition behind net zero goals with a significant ramp up in commitments from countries (and corporate actors) in the run-up to COP26, but will equally require significant changes to policy in order to meet these commitments.

Climate Action Tracker (CAT) assessments show that the temperature estimates for end-of-century warming have been falling for both the targets and real-world emissions projections.

The run-up to COP26 has seen a significant inflection in action

It is clear the Paris Agreement is driving climate action. According to the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), commitments to net zero have doubled in the last year and the pace continues to accelerate16. This is true at a corporate, national and regional level. Climate Action Tracker (CAT) assessments show that the temperature estimates for end-of-century warming have been falling for both the targets and real-world emissions projections. End-of-century warming estimates for real-world emissions have fallen by 0.7°C in the five years to December 2020 and the recent wave of net zero targets, if they are met, which has put the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C within striking distance. Climate Action Tracker has calculated that global warming by 2100 could be as low as 2.1°C as a result of all the net zero pledges announced as of November 2020.

The announcement by China in September 2020 that it intends to reach carbon neutrality before 2060 reduced the CAT end-of-century warming estimate by 0.2 to 0.3°C alone. Assuming carbon neutrality in the USA by 2050, as proposed by President Biden, would reduce warming by another 0.1°C117. This shows the power of collective action. Coordinated and effective involvement from governments, companies and consumer behaviour has the capacity to continue to improve trajectory. This spirit of co-operation and ambition needs to be further harnessed in the run-up to COP26 and continue through the implementation phase to make net zero a reality. Recent momentum means that 51% of current emissions are now backed by net zero pledges covered under law or in discussion;18 this rises to 63% following the announcement that the United States is re-joining the Paris Agreement.

The main caveat is that the majority of these pledges have not been fully codified in law or have targets set to enable countries to achieve them19. There also remains a substantial gap between what governments have promised to do and the total level of actions and policies they have undertaken to date20. We agree with the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) that the 2020s must be the decisive decade of progress and action on climate change21. Encouragingly the legal standing is changing. In 2019 for example, the UK became the first major economy to make net zero emissions law and has subsequently been followed by others including France, New Zealand and Denmark21. Once enacted, the laws and goals need explicit targets and mechanisms for action. For example, the CCC estimates that for the UK to meet its goals by the early 2030s, every new car and van, and every replacement boiler must be zero-carbon; in addition, by 2035, all UK electricity production must be zero carbon.21 The wider impacts of these economic shifts and the challenges associated with them will be covered later in the series, but are a key focus for investors.

Conclusion

The run-up to COP26 hosted in Glasgow later this year is hugely significant in cementing progress towards net zero.

Policy makers should be emboldened by signs of progress on both the emissions trajectory and of the falling cost of getting to net zero. They should be ambitious in their target setting in alignment with a 1.5°C world and confident that with the required urgency there is a credible path to addressing the climate crisis.

Click to display all sources >>

1 Source: https://www.theworldcounts.com/challenges/climate-change/global-warming/global-co2-emissions/story

2 Source: https://www.mercer.com/our-thinking/wealth/climate-change-the-sequel.html

3 Source: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

4 Source: https://www.research.hsbc.com/C/1/1/254/RSNbxjg

5 Source: Martin Currie: Climate Change an Inevitable Risk 04/07/20: https://www.martincurrie.com/uk/insights/long-term-investment-institute/investment-institute-insights/Climate-change-an-inevitable-risk

6 Source: https://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/news/what-is-net-zero/#:~:text='Net%20zero'%20refers%20to%20achieving,taken%20out%20of%20the%20atmosphere.&text=In%20 contrast%20to%20a%20gross,allows%20for%20some%20residual%20emissions

7 Source: https://eciu.net/analysis/briefings/net-zero/net-zero-why-1-5%C2%BAc

8 Source: https://www.wri.org/blog/2018/10/half-degree-and-world-apart-difference-climate-impacts-between-15-c-and-2-c-warming

9 Source: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/SREX-Chap3_FINAL-1.pdf

10 Source: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/

11 Source: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/

12 Source: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/02/SPM2.png

14 Source: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-why-the-ipcc-1-5c-report-expanded-the-carbon-budget#:~:text=The%20newly%20published%20Intergovernmental%20Panel,it%20at%20 around%20three%20years.

15 Source: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/P-9-2020-000530_EN.html#:~:text=The%20UN%20Climate%20Change%20Conference%20(COP26)%20in%20 November%202020%20will,Agreement%20enters%20its%20implementation%20phase

16 Source: https://unfccc.int/news/commitments-to-net-zero-double-in-less-than-a-year

17 Source: Ibid: https://newclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CAT_2020-12-01_Briefing_GlobalUpdate_Paris5Years_Dec2020.pdf

18 Source: https://newclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CAT_2020-12-01_Briefing_GlobalUpdate_Paris5Years_Dec2020.pdf page 6

19 Source: https://eciu.net/netzerotracker

20 Source: https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/

21 Source: https://www.theccc.org.uk/2020/12/09/building-back-better-raising-the-uks-climate-ambitions-for-2035-will-put-net-zero-within-reach-and-change-the-uk-for-the-better/

Regulatory information and risk warnings

This information is issued and approved by Martin Currie Investment Management Limited (‘MCIM’), authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. It does not constitute investment advice. Market and currency movements may cause the capital value of shares, and the income from them, to fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested.

The information contained in this document has been compiled with considerable care to ensure its accuracy. However, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made to its accuracy or completeness. Martin Currie has procured any research or analysis contained in this document for its own use. It is provided to you only incidentally and any opinions expressed are subject to change without notice.

This document may not be distributed to third parties. It is confidential and intended only for the recipient. The recipient may not photocopy, transmit or otherwise share this [document], or any part of it, with any other person without the express written permission of Martin Currie Investment Management Limited.

The document does not form the basis of, nor should it be relied upon in connection with, any subsequent contract or agreement. It does not constitute, and may not be used for the purpose of, an offer or invitation to subscribe for or otherwise acquire shares in any of the products mentioned.

The views expressed are opinions of the Martin Currie analysts as of the date of this document and are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or analysts of the firm as a whole. These opinions are not intended to be a forecast of future events, research, a guarantee of future results or investment advice.

Please note the information within this report has been produced internally using unaudited data and has not been independently verified. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure its accuracy, no guarantee can be given.

The analysis of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors forms an important part of the investment process and helps inform investment decisions. The strategy/ies do not necessarily target particular sustainability outcomes.

For institutional investors in the USA:

The information contained within this presentation is for Institutional Investors only who meet the definition of Accredited Investor as defined in Rule 501 of the United States Securities Act of 1933, as amended (‘The 1933 Act’) and the definition of Qualified Purchasers as defined in section 2 (a) (51) (A) of the United States Investment Company Act of 1940, as amended (‘the 1940 Act’). It is not for intended for use by members of the general public.

For wholesale investors in Australia:

This material is provided on the basis that you are a wholesale client within the definition of ASIC Class Order 03/1099. MCIM is authorised and regulated by the FCA under UK laws, which differ from Australian laws.